Erdogan threatens the Europeans to send terrorism to Europe

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s decision to remit foreign citizens who supported the Islamic State is handing Western Europe a drag it had hoped to avoid.

Faced with fierce widespread opposition to the repatriation of such detainees and fears over the long-term threat they might pose back home, European leaders have sought other ways to prosecute them — in a world tribunal, on Iraqi soil, anywhere but on the Continent.

Turkey recently sent a dozen former Islamic State members and relatives to Britain, Denmark, Germany, and, therefore the US, and Mr. Erdogan says hundreds more are right behind them.

The unexpected issue for Europe might be the outcome of President Trump's choice to pull back American powers from northern Syria, which made room for Turkey to require control of an area additionally the same number of the Islamic State individuals who had been held there in Kurdish-run detainment facilities or confinement camps.

The issue is further complicated by the very fact that almost two-thirds of the Western European detainees, or about 700, are children, many of whom have lost one parent, if not both.

Now that more of the former fighters are in Turkish hands, Mr. Erdogan has not hesitated to use the threat of returning them as leverage over European countries who are deeply critical of his incursion, and who have threatened sanctions against Turkey for unauthorized oil drilling within the eastern Mediterranean off Cyprus.

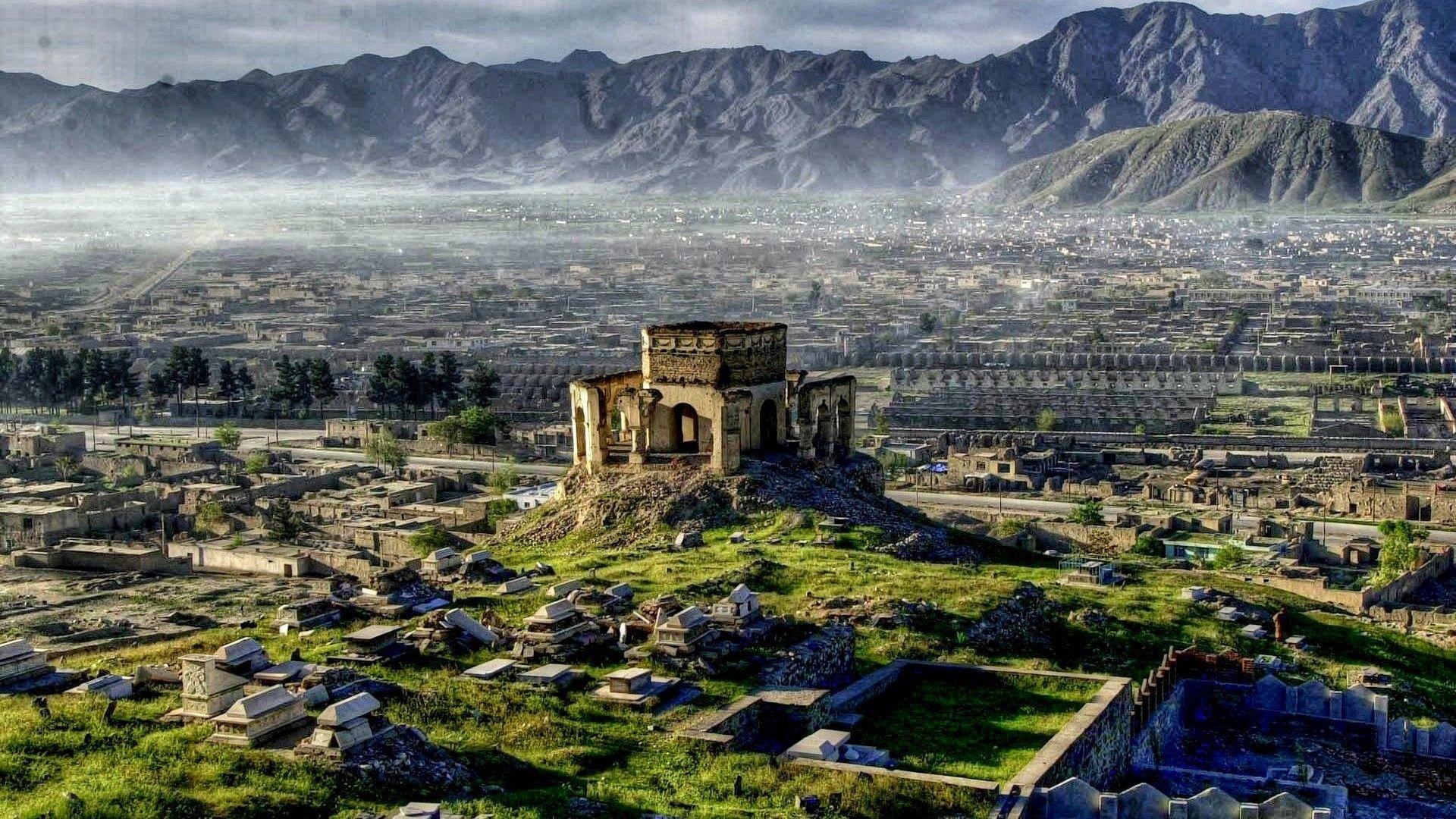

The destiny of the former fighters and their families has become at this point a ground of dispute among Turkey and Europe, which is now paying Mr Erdogan's administration billions of dollars to stem the progression of refuge searchers from clashes in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan.

Turkey is already home to some three million refugees from the Syria conflict, and Mr. Erdogan has decided to lighten his country’s load. But his real intent remains unclear: Does he choose to remit all foreign fighters to Europe? Or is he opening the spigot, with the threat of a flood to return, to wring concessions from Europe?

What is clear is that with limited military reach in Syria, European nations are ever more susceptible to Mr Erdogan’s whims. Turkish officials say that Turkey now holds 2,280 Islamic State members from 30 countries, which all of them are going to be deported.

The problem isn't Europe’s alone. Turkey deported an American it described as an Islamic State member, Muhammad Darwish Bassam, to the US. Last week, a federal judge within the US ruled that an American-born woman who joined the Islamic State in 2014 wasn't an American citizen, potentially thwarting her return.

But the numbers and risks for Europe are far higher than for the US. One thousand one hundred citizens of nations in Western Europe are believed to be detained in northern Syria in territory once controlled by the Islamic State, consistent with a recent study by the Egmont Institute.

Their potential return has confronted European justice systems with competing security and civil liberties demands as they plan to vet returnees, decide whether to detain them, and build cases on potential crimes that always happened hundred of miles away on remote Syrian battlefields.

France, the Western European country, with the foremost detainees in Syria, is preparing to require back a few former Islamic State members. The Netherlands has also agreed to require back a number of its citizens.

Recently, a 26-year-old man suspected of being an Islamic State fighter was arrested after landing at London’s Heathrow Airport on a flight from Turkey.

That same day, seven members of a German-Iraqi family arrived in Berlin from Turkey, from which that they had been deported after several months in custody over suspected links to terrorism.

The father was detained, but the opposite relations were allowed to return to their homes.

German officials said they believed about 130 people left the country to hitch ISIS, 95 of whom were German citizens and had the proper to return to the country. Nearly a 3rd of the Germans are under investigation by federal prosecutors.

French officials said there had been no change in French policy, which opposes repatriation from Syria.

But pressure has been building, and security experts and a few officialdom have increasingly warned that the repatriation of militants — and their processing in European courts and detention in prisons — would be the sole thanks to ensuring Europe’s safety.

The deteriorating situation in northern Syria, some experts say, further increases the necessity for an orderly repatriation to Europe.

- 2020 Jan - 13